中文

中文

(預警:本文部分文字和圖片可能令人不適,包括對大屠殺的描述和屍體照片)

extermination camps set up by Nazi Germany like Auschwitz-Birkenau, a special unit of Jewish prisoners called Sonderkommandos were tasked with guiding unsuspecting fellow Jews to the gas chambers, and removing and cremating dead bodies. About 100 Sonderkommandos survived the holocaust, and much of what we know about how the killing machine actually worked comes from their testimony. On the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz by Soviet troops, this is their story.

特遣隊(納粹德國集中營裏負責處理死者的囚犯分遣隊),特遣隊員

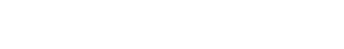

“I worked in the crematoria. I took people (dead bodies) from the gas chambers to the ovens,” says Dario Gabbai.

The former Auschwitz concentration camp prisoner was talking about removing the corpses of Jewish victims and incinerating them.

Gabbai, now 98 years old, is one of the last eyewitnesses to the Final Solution – the Nazi plan to eliminate Jews from Europe which culminated in the murder of six million Jews.

On the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau, this is the story of the Sonderkommandos, Jewish prisoners forced to assist in the Holocaust.

To speed up the murder, the Nazis set up extermination camps like Auschwitz-Birkenau and created a special unit called Sonderkommando.

It consisted of Jewish prisoners deported to Auschwitz from 16 different countries, whose labour fed the killing machine.

“It is something I will never forget. I was lucky to survive,” says Gabbai.

After the liberation of Auschwitz on 27 January 1945 by Soviet forces, many survivors expressed their ordeals in books. But very little was heard from the few Sonderkommandos that made it out.

In the 1980s, Israel-based Holocaust historian Professor Gideon Greif started the long task of uncovering the mystery of the Sonderkommandos.

“One of my goals was to improve their image. When I started the research, they were considered collaborators and murderers. But they were the victims, not perpetrators,” Dr Gideon Greif told the BBC.

Prominent Auschwitz survivor Primo Levi wrote in “The Drowned and the Saved” that the creation of Sonderkommando was the most satanic crime of Nazism. Dr Greif agrees.

“It was the deliberate decision by the Germans to employ them. They also wanted the Jews to share the blame. This is a very cruel idea. They wanted to blur the difference between criminal and victim.”

Dr Greif documented the experience of 31 Sonderkommandos in his first book about them, We Wept Without Tears.

Sonderkommando members were forced to assist in the process of killing. The SS did the actual killing.

They had to conduct a cavity search for implants like gold teeth and hidden valuables before they disposed of dead bodies.

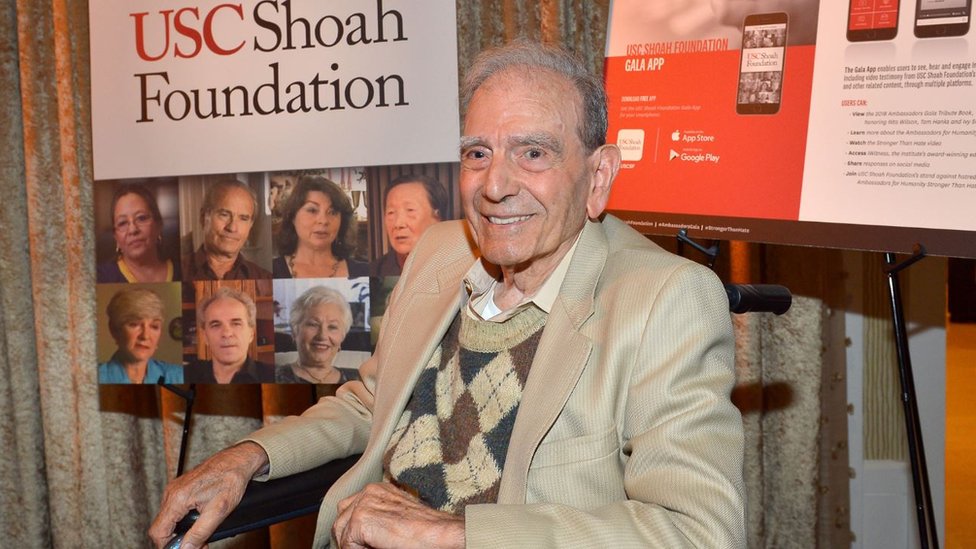

Very few images exist of Sonderkommandos in a working context in Auschwitz, but after the camp’s liberation the Soviets staged various images recreating the horrors they went through.

Gabbai had the specific task of cutting and collecting the hair of murdered women.

Decades later he recalled how he felt, while talking to a US organisation dedicated to interviewing Holocaust survivors, the USC Shoah Foundation.

“I said to myself how can I survive? Where is God?” Gabbai wondered.

A Polish man told him to stay strong and he took that advice seriously.

“I said to myself, I am a robot… close your eyes and do whatever has to be done without asking too much.”

Gabbai couldn’t afford to disobey orders – anyone found to be a bit slow or inefficient was brutally punished.

Sometimes the SS guards inspected dead bodies on their way to the incinerators. If they spotted a gold implant which the Sonderkommandos had missed, the person responsible might be thrown alive into the burning pits.

Other punitive measures included shooting, torture, beating and being rolled naked on gravel.

These were carried out in the presence of other Sonderkommandos to intimidate the whole group.

The job offered little protection. Nazis used to kill the members of the Sonderkommando about every six months and bring in new recruits.

“They were in a state of constant shock. They saw thousands of Jews murdered every day. It was a big challenge to remain alive,” Dr Greif says.

Yet, many like Gabbai not only survived but provided information about the actual working of the death factory.

“They closed the doors. Then the SS threw the Zyklon B (Cyclone B) from three four openings above. It took about four five minutes to die, except people in the front where the gas was coming. There it took a couple of minutes.”

Zyklon B was delivered to the camps in crystal pellet form. As soon as the pellets were exposed to air they turned into poisonous gas and started killing people.

One of the Sonderkommandos documented by Dr Greif was Ya’akov, Dario Gabbai’s brother.

Ya’akov saw two of his cousins turning up at the gas chamber. He instructed them to sit close to where the gas was released for a quick, painless death. He told Greif, “Why should they suffer so much?”

Dr Greif says many who worked in the Sonderkommando unit were irrevocably changed.

“In order to prepare or service such a death factory they became emotionless. That doesn’t mean they were not good – or evil – people. Some of them told me about what they did to help to maintain the dignity of the Jewish victims,” he adds.

Josef Sackar was the first Sonderkommando Dr Grief met in 1986. Sackar was often deployed in the place where women were asked to undress.

“I drifted my head to other direction and made sure they didn’t get very embarrassed,” Sackar told him.

Shaul Chasan had to remove the bodies of the dead from the gas chamber and place them in the lifts which would take them to the crematoria. He told Dr Greif how he always made an effort to make sure that the bodies were not dragged over the dirt and debris on the floor of the gas chambers.

Most of the Sonderkommandos were orthodox Jews. Greif says they managed to pray three times a day, as stipulated in Judaism, on most of the days.

Amazingly they were able to pray together whenever they got the minimum number of ten required as per religious laws.

When the camp guards were not around, Sonderkommandos even recited the Kaddish – a prayer traditionally recited in memory of the dead – during the cremation process.

Fewer than 100 Sonderkommandos, recruited during the deportation of Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz, managed to survive World War Two.

Israel’s Holocaust memorial, Yad Vashem notes how the killings went up after the deportation of Hungarian Jews began in May 1944. “In just eight weeks, some 424,000 Jews were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau.”

The killing rate far exceeded the capacity of the crematoria. But the German officer in charge of the crematoria, Otto Moll, was unrelenting and he ordered the Sonderkommandos to dig up burning pits.

A clandestine photo taken by a Sonderkommando clearly shows bodies being incinerated in an open air pit – it later provided valuable evidence.

Sonderkommando Shlomo Dragon witnessed rare acts of defiance and narrated one such incident to Dr Greif.

“One woman refused to undress completely, and when an SS man [the German units who ran the camps], Schillinger, pointed his gun at her and demanded she remove her undergarments, she took her bra off, waved it in his face, then hit him, making him drop his gun. The woman quickly grabbed it, aimed, and fired, killing Schillinger.” He told Greif.

The woman widely identified as a Polish dancer Franceska Mann gained a legendary reputation after her death.

Another Sonderkommando saw how a group of naked Polish children started singing “Shema Yisrael”, a Jewish prayer, and entered the gas chamber with perfect discipline.

Sonderkommandos were given comparatively more food and better living conditions than the rest of the inmates, who were given watery soup. They also had the opportunity of taking and using the clothes of the victims. Dr Greif says these were “marginal incentives”.

They were also housed separately and monitored all the time. Yet they managed to put up a fight which is known as Sonderkommando rebellion.

“Two brothers were involved in the planning of the Saturday 7 October 1944 uprising. It was a Jewish revolt. It was a story of courage. It should be written in golden letters,” says Dr Greif.

On that day some Sonderkommando prisoners attacked their SS guards using stones, and set fire to one crematorium. It was swiftly stamped out, and 451 Sonderkommandos were shot dead.

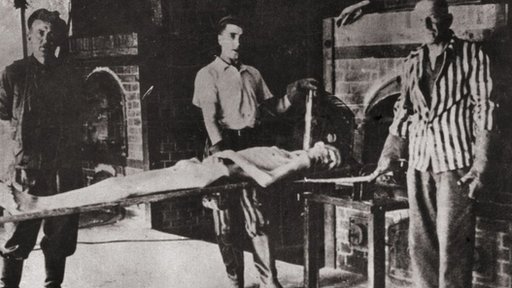

Other Sonderkommandos like Marcel Nadjari recorded their anger on scraps of notepaper.

“I am not sad that I will die, but I am sad that I won’t be able to take revenge like I would like to,” Nadjari wrote in November 1944.

The ashes from each adult victim weighed about 640 grams, according to his notes.

The Greek Jew then hid his 13-page manuscript in a thermos flask, which he sealed with a plastic top. He then placed the thermos in a leather pouch and buried it.

Notes left by Nadjari and others were recovered years later and painstakingly deciphered. These are now known as the Scrolls of Auschwitz.

They provide valuable insight into the scale of the crime.

After the war some Sonderkommando members took on their former guards in court.

Henryk Tauber testified against the SS commander, Otto Moll.

“On several occasions, Moll threw people into the flaming pits alive,” Tauber recalled during the trial by an American Military Tribunal.

Moll was eventually convicted and hanged for his role in a ‘death march’.

Fearing defeat the SS started evacuating the camp from mid-January 1945. Close to 60,000 starving and half-naked inmates were forced to walk through snow in temperatures of -20C to towns more than 50km away.

Those who couldn’t keep up were shot and killed.

Yet, many criminals were never punished. Of a total of about 7,000 staff at Auschwitz, only around 800 faced the force of law, according to ‘Auschwitz’, a BBC/PBS documentary series.

The Auschwitz-Birkenau complex, is the site of the biggest mass murder in human history – an estimated

1.1 million people

were killed, of whom more than 90% were Jews. This is more than the loss suffered by the UK and US in the entire war.

Dr Greif estimates the number of those killed to be over 1.3 million. He insists that the pursuit of justice should not slow down.

“No German Nazi criminal deserves to die in bed.”

He has often travelled to European courts to testify against suspected Nazi criminals.

“The German attempts to destroy all proof of their crimes led to a documentary vacuum, that can only be filled by the memories of the survivors,” says Greif.

He says his biggest achievement is changing that perception about Sonderkommandos.

“Nobody will dare to call them collaborators now,” says Dr Greif.

The lone surviving Sonderkommando witness, Gabbai, now lives in Los Angeles and is too ill to speak. Five years ago during his visit to mark the 70th Anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, he spoke to the BBC.

“I said (to myself) this war is going to end one day and when it ends I can survive and tell the stories to the world.”

本網頁內容為BBC所提供, 內容只供參考, 用戶不得複製或轉發本網頁之內容或商標或作其它用途,並且不會獲得本網頁內容或商標的知識產權。

25/09/2025 05:00PM

25/09/2025 05:00PM

25/09/2025 05:00PM